Ancient Greek Art: Seeing Senility and Disability Through the Eyes of the Ancient Greeks

Alexandra Mavraeidi

5/8/20243 min read

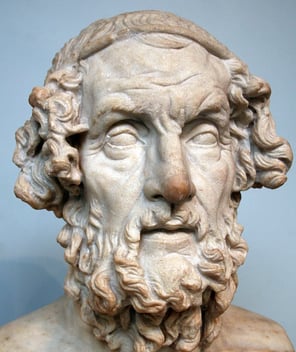

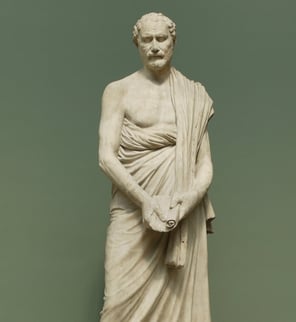

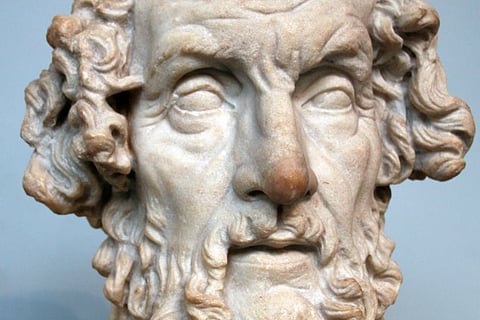

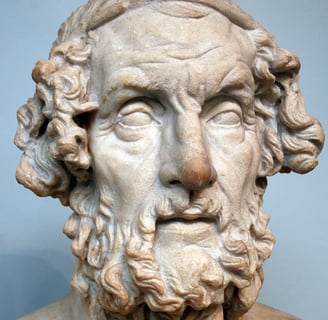

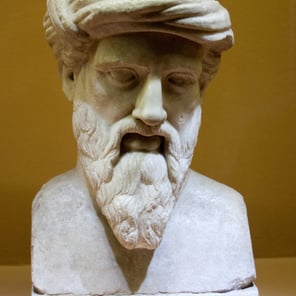

Ancient Greek art is renowned for its beauty and significant influence on the development of Western art. From its simplistic and abstract expression in the 8th century B.C. to its pursuit for diversity and expressiveness in the 1st century B.C., ancient Greek art evolved through the centuries, leaving us remarkable works of art that continue to inspire artists and art enthusiasts to this day.

These works of art, however, are not mere exhibits inside museum walls that were just lucky enough to survive the passage of time; they are time machines. Yes, you read that right. They are time machines that help historians take a glimpse—however small that is—of the people that created them, their values, and their beliefs. It is true that idealised beauty was highly valued in ancient Greek society and art, but that leads us to a big question: What about the people who were not ideal enough?

Archaic Period

Classical Period

In antiquity, the social response to the disabled was determined by religion and the Greek standards for a citizen’s public life. Ugliness and deformity were regarded as signs of divine disfavour, while the abstention from warfare and the affairs of state was looked down upon. The treatment of the handicapped varied depending on the city-state. In Sparta the abandonment of deformed infants was required by law and the people were generally very harsh towards those who were not capable because strength and masculinity were unique markers of Spartan identity. In Athens and Boeotia people seem to have been more cognizant of disabilities and the city provided a maintenance payment for the disabled who couldn’t make a living on their own, so that they wouldn’t fall victims to wealthy politicians.

The majority of Greek elderly, even if acquiring a form of disability, still remained mentally alert and took part in the economic well-being of the household. That was mainly due to the short life expectancy of the people who usually died in their fifties. In all city-states the elderly were respected and their desertion by their children instigated severe penalties: incarceration in Delphi, fines and partial deprivation of citizen rights in Athens and more. Be that as it may, Greek physicians were not invested in finding methods of alleviating ailments of the old, nor was there provision to facilitate their participation in ceremonies and rituals, same as for the disabled.

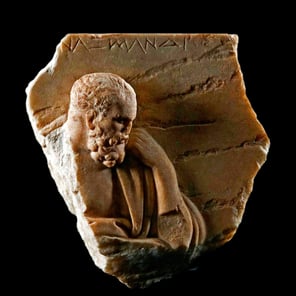

As the centuries progressed, ancient Greek art became more inclusive and the portrayal of the disabled and the elderly more frequent. The artists' goal was not to criticise the disadvantaged position they held in society, but to project it as a mere characteristic of the subject. Sometimes, they attributed wisdom or added an anecdotal tone to their work, while other times they just respected tradition and did not cut a disability away from the subject. All in all, the elderly and the disabled might have been treated better in some cases, but in most cases, they continued to suffer in silence, demanding nothing from society and hiding away as if they were a source of shame, a stain in the city’s image.

Further Reading

Penrose, Walter D. “The Discourse of Disability in Ancient Greece.” The Classical World, vol. 108, no. 4, 2015, pp. 499–523.

Palagia, Olga, editor. Ancient Greek and Roman Art and Architecture. Volume 1, Handbook of Greek Sculpture /, De Gruyter, 2019.

Gardner, Helen et al. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: A Global History. 15th Editiong, Student ed., Cengage Learning, 2016.

Smith, R. R. R. Hellenistic Sculpture: A Handbook. Thames and Hudson, 1991.

Osborne, Robin, and Princeton University Press. The Transformation of Athens: Painted Pottery and the Creation of Classical Greece. Princeton University Press, 2018.

Garland, Robert. Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks. Pbk. ed., Hackett Pub, 2008.